Are Japan’s dismissal regulations not strict compared to international standards?

During the recent LDP leadership election, a female candidate known for her strong conservative views remarked that “Japan’s dismissal regulations are not that strict when compared internationally.”

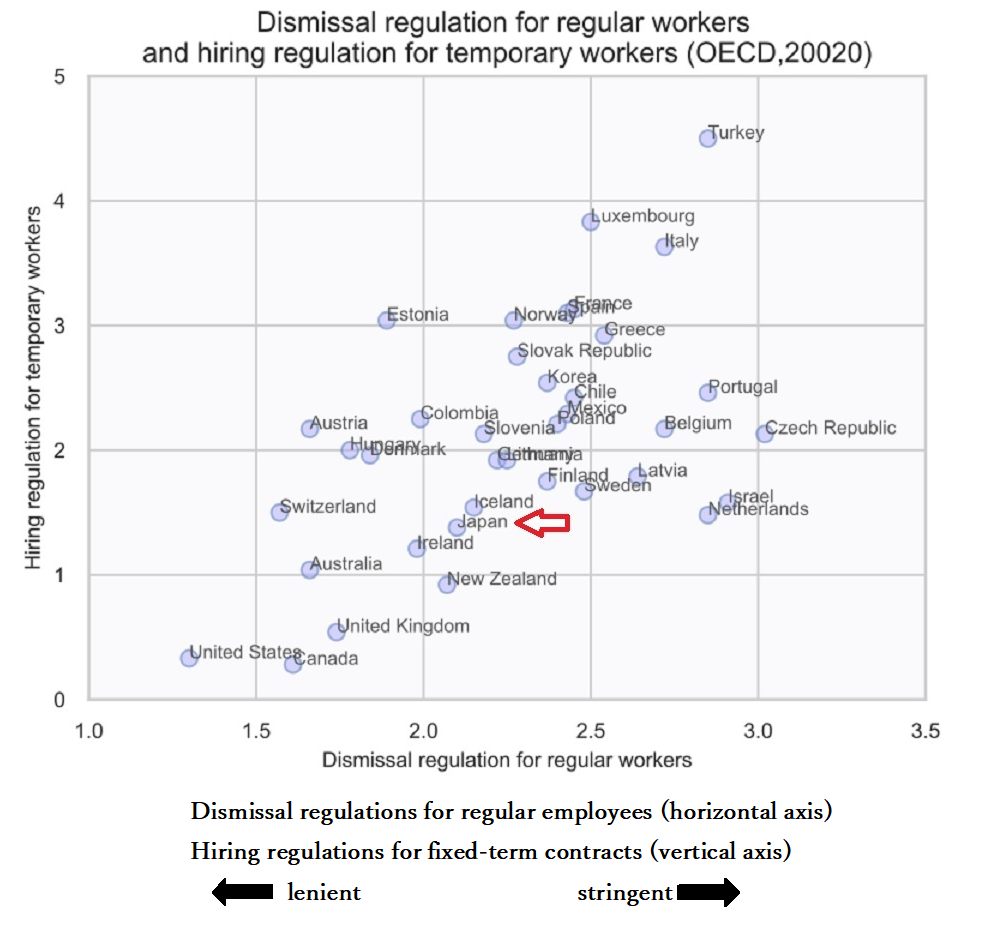

Her statement seems to be based on the OECD Employment Protection Legislation (EPL) indicators.

I apologize for the somewhat hard-to-read graph below, but it is an international comparison from the OECD regarding the dismissal regulations for regular employees and fixed-term contract workers. The vertical axis represents regulations for fixed-term workers, and the horizontal axis represents regulations for regular employees. Higher values indicate stricter regulations, while lower values suggest more lenient regulations.

Now, can you spot Japan? I’ve marked it with an arrow, positioned between Ireland and Iceland. From this overview, it does seem that Japan’s dismissal regulations are slightly more lenient compared to the OECD average. So, is the female candidate’s view correct?

I delved a bit deeper into this survey. The OECD appears to have set 24 specific indicators for dismissal regulations and used these to assess the labor laws of OECD countries.

When I checked the specific items for Japan in the OECD’s survey, the results for some items were as follows:

- Notice period for dismissal: Employers are required to give at least 30 days’ notice or pay an average wage equivalent to 30 days or more. Verbal notice is sufficient, and a written explanation of the reason for dismissal is provided only if requested.

- Dismissal notice period based on length of service: No specific regulations exist in Japan that adjust the notice period based on the employee’s length of service. Regardless of tenure, the notice period remains 30 days.

- Severance pay based on length of service: In Japan, there is no legal obligation to pay severance based on length of service.

If one interprets these three results literally, it’s easy to conclude that Japan’s dismissal regulations are quite lenient.

However, we know the reality. These OECD survey results are based on Japan’s Labor Standards Act, but the Act itself is not sufficient to address dismissals in Japan.

In practice, can an underperforming employee really be dismissed with just 30 days’ pay? No one would agree with this.

First, in Japan, the reasons for dismissal are rigorously examined, and efforts to avoid dismissal are repeatedly reviewed. Even when dismissal becomes possible after such scrutiny, it is customary to provide special severance pay. This severance is based on length of service, with longer tenure generally resulting in higher severance amounts. At PMP (My consulting firm: People Management Professionals), when consulting on dismissal cases for companies, we advise that at least one month of severance per year of service, with a of three months, should be provided. Furthermore, when the case goes to court, severance expectations tend to rise.

This is the reality, but such practices are not mentioned anywhere in the Labor Standards Act or other labor laws in Japan.

On a side note, what frustrates me most is that the person who cited this OECD survey to outmaneuver her rival candidate holds the position of a member of the Diet, the highest legislative body in our country.